Source: Pexels

Source: Pexels

On a wintry night, a BBC journalist sat beside a young woman, who was lying on a busy street of London. She has been rough-sleeping for almost two years. The journalist asks, “Do you feel lonely?” “Yes. Very. It is not the rain, cold nights or any of that stuff. For me, the worst part about being here is not being seen. People will walk past and you will see them look, but they look away rather quickly,” the woman replied. “What can we do?” was the second question, to which the woman put forth a counter question, “Who are ‘we’?”. “We, the government, I and the people,” the journalist replied. The young woman was laconic. She replied, “Care.”

Stateless, homeless, and often invisible

This story is universal. From London to New York and Moscow to Mumbai, homelessness is evident in numbers. While the UK has at least 320,000 homeless people, New York City, which has been the epicenter of COVID-19 outbreak in the US, alone has close to 80,000 homeless people, among the highest in the country. According to the Census 2011, India is home to more than 1.7 million homeless residents. This figure has been questioned by several advocacy organisations that estimate the population of urban homeless alone to be about four million. Delhi is estimated to have around 150,000 – 200,000 homeless people, of which at least 10,000 are women.

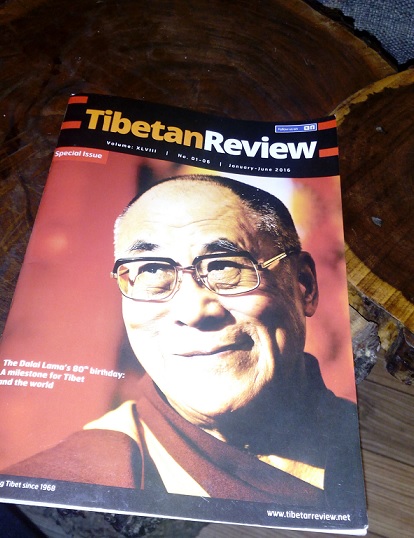

Then there are others. Millions of people are growing up (and growing old) in refugee camps across the world. If we shudder at the idea of community transmission of novel coronavirus in Dharavi or Kibera, can we even begin to imagine the state of affairs in Kutupalong—the world’s largest refugee camp in Bangladesh with more than 630,000 people—or the notorious Al-Hol camp in northeast Syria? According to the UNHCR, there are around 70.8 million displaced people around the world, among them nearly 25.9 million people are refugees. These people are not just denied a nationality, but also access to education, health care and employment.

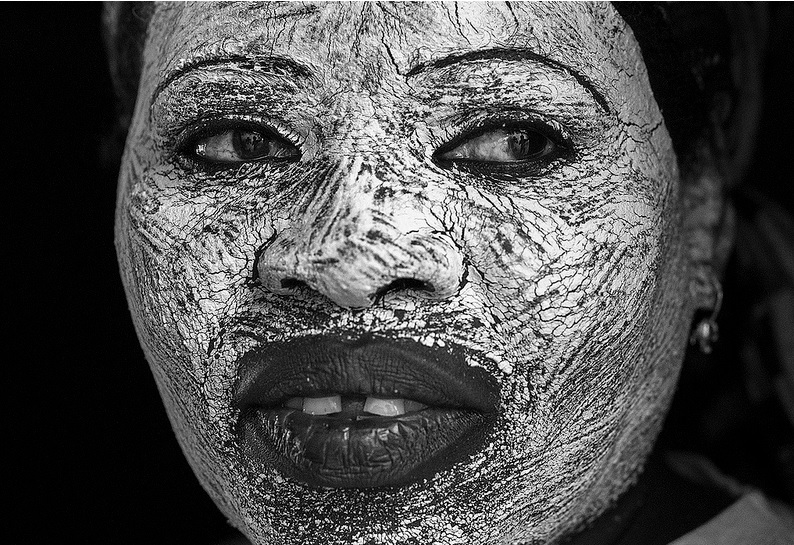

It is not just their sheer number, but also the chronic stress that they live in is hard for us to wrap our heads around. The people we see (or don’t see) under the bridges, on the road dividers, along the railway lines and inside the wobbly tents are squeezed between structural fault lines. Minors pick up drinking habits after their parents. Women are abused; they are too afraid to sleep at night. They bear the brunt of cold and heat. Their mental health takes a serious beating. On top of all this is the indignity thrown at them by the locals.

Poverty tax adds to ignominy

Some of these people find shelter in informal settlements, where they have to often pay dramatically higher costs for basic services, which is referred to as ‘poverty tax’, according to a study conducted by the Tata Centre for Development at University of Chicago in collaboration with other research and advocacy organisations, including the Mumbai-based Pukar. The study, which covers 24 slums across seven states, posits that this poverty tax affects social mobility and a range of socio-economic outcomes.

In some informal settlements, where there is no public provisioning of basic services, prices of electricity appear to be several times higher than market rates and water prices up to 100 times higher, the initial findings of the study suggest. It also points to a worrisome trend: higher cost of basic services in these informal settlements leads residents to use less of those services than would be optimal. In the time of Covid-19 pandemic, washing hands with water even after using toilets or before having food is not realistic for them.

Mainstreaming the marginalised

While the actual extent of homelessness may not be known for some time, four million could be a good starting point. Assuming that 25 per cent of the 4 million homeless people in the country are women, can we not absorb them where we need them the most? The primary health care workforce. They could be trained to become ASHA workers—the frontline change makers and backbone of primary health care. So far, their contribution in improving health outcomes is undeniable.

A large chunk of remaining three million could also make meaningful contribution to India’s well-being: making the country water-secure. Lately, building water harvesting structures has gained momentum in the country, which has seen sporadic cases of severe water crisis and apprehends bleaker times ahead. MGNREGA—the largest rural employment guarantee scheme in the country, and perhaps in the world–can come to their rescue. Under this scheme, these people can be deployed in building contour trenches, percolation tanks, and desilting dug wells and other water collection chambers. Importance of such activities need not be harped upon.

Having said that, what would be the cost implications for the government? Currently, there is a huge difference in wages (from INR 190 – INR 309 per day) paid to MGNREGA workers across states. Taking INR 250 as average per day salary for 100 man days for 2 million people (erstwhile homeless), the government will have to cough up INR 5,000 crore, which is little more than 8 per cent of total outlay for MGNREGA in 2020-21 Union Budget. That’s not much if we think of positive outcomes: it will lead to reverse migration, generation of livelihood for so many people, ensure less water stress during our agricultural seasons, and hopefully, reduce the number of begging gangs in cities.

Source: Pexels

Source: Pexels

“For a long time I missed home; it was a missing tooth,” said Sholeh Wolpe, an award-winning Iranian-American poet and literary translator. She was recently in India to talk about her experience of living an exiled life. She left Iran at the age of 13 when the Iranian Revolution stifled freedom and fettered people’s dreams.

“For a long time I missed home; it was a missing tooth,” said Sholeh Wolpe, an award-winning Iranian-American poet and literary translator. She was recently in India to talk about her experience of living an exiled life. She left Iran at the age of 13 when the Iranian Revolution stifled freedom and fettered people’s dreams.